It does not look too shabby for a hundred-year-old: slender, elegant, and pale. It stands there and would not even flinch, like it did not under the pressure of the first ironic glances. It was the beloved child of a visionary, a child of love for what’s new, and of faith in the impossible. And yet the city residents who usually do love novelties and crave the impossible, no one wished it well. Spiteful New Yorkers who witnessed its birth were ready to beton how far the dust would spread when it falls. They did not believe that the openwork steel structure could withstand the weight of twenty-one-stories-high stone-covered facade. However, it has not fallen then, nor later – in spite of countless dark prophecies of catastrophic films, in which it was often shown in ruins, a victim of sudden disaster or the fury of a giant lizard.

It was baptized after its daddy (who also was its first tenant), the inventor of steel frames and the builder of first New York and Chicago skyscrapers, George Fuller. But the New Yorkers quickly found a new name for it, derived from the bizarre shape of the building, erected on a triangular patch of land where unruly, crooked Broadway intersects with the exquisite Fifth Avenue: The Flatiron Building.

Why of many objects that could be associated with its unusual shape something so pedestrian was chosen? Maybe the building’s beauty was so shocking from the get-go that it had to be somehow identified with a well-known, familiar reality in order to be dealt with. New Yorkers are not to eager to show their emotions, and this incredible, ornate building covered with lace-like stone carvings and adorned with rectangular and semicircular windows, and segmented semi-columns modeled on Renaissance armories would surely have move them, if it only was named The Column or The Chocolate Box.

The very location of this peculiar building is in many ways incredible. Flatiron occupies a tiny triangle at the intersection of the two most important avenues in the city. This sliver of land is cut off from Downtown by a wide ribbon of 23rd Street, and separated from the nearby Madison Avenue by a park where one can find refuge from the downtown bustle. Here, New York of the Knickerbockers – the city of descendants from the first European settlers, of folks marked by their strong connection to history and tradition – ends abruptly. From 23rd Street up to the north, where neither the 19th nor the earlier centuries have ever set their foot before, everything begins to go up even faster, and with more categorical resolve. But before the hurried Broadway gallops into Herald Square and then rushes right into the neon light glow of Times Square, for a few blocks, between the 20s up to the 34th Street, it will remain the most ordinary of Garment District walkways, lined by haberdashery and the Korean perfume shops. In the Flatiron area, the legendary Fifth does not yet amuse with its glamour, as if it was just getting ready for its spectacular entrance into the Forties, and about to shine in its full glory there. Here it is merely a bourgeois avenue of banal, uninteresting houses.

Only the 23rd Street is teeming with life; and it is partially due to the Flatiron Building’s presence. Apparently, since this peculiar building was erected, a draft of epic proportion started around – and it became almost legendary. The wind was said to be gaining such strength in the deep tunnel in between the buildings that it made long ladies’ dresses drift way up as they were passing through. The construction workers busy with completion of the Fuller Building façade gathered up in groups to watch it, laughing and whistling with delight, only to be eventually dispersed by unenthusiastic patrols of the New York’s Finest, doing their routine rounds of the neighborhood. It was the cops who forged the expression to describe this wayward wind (and the interesting phenomenon caused by it) – once fashionable, and nowadays almost forgotten expression: 23 Skidoo.

Each time my strolls take me towards the Flatiron Building, I get to think of those floating Art Nouveau dresses, and of gentlemen photographers crossing the green square, Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Steichen, who captured so exquisitely the late autumn evenings of the early 20th century. Captivated by exceptional beauty of the Flatiron, they placed their bulky cameras among the naked trees and took: the most beautiful portraits ever made of this magical edifice. In Stieglitz’s pictures, the building is seen in a bizarre, flattened perspective from the north-east side; it looks like a town hall of Flatland, the fantastic, two-dimensional land. In Steichen’s pictures, the structure looms in a sepia-toned fog like a spectre or a gigantic tchotchke on an ogre’s desk: a whimsical, round-edged object, beautiful and useless at the same time. People – those dark silhouettes, barely visible in the dim light – do not dare to come closer. Only leafless trees stretch their curious branches, as if asking: what is this strange stone trunk, growing on the street corner?

While the city around constantly plays with new styles, dresses itself up and paints itself over, the Flatiron Building hasn’t changed alone bit over the last century. It is stuck here like a dormant ship, a giant steam liner, a banner-bearer of an unknown country. A stone vessel, temporarily moored at the corner of 23rd Street and Broadway, is pinned to the Manhattan rock with a heavy anchor of its tenants’ luggage: weighty file cabinets, workbooks, bookkeepers’ records. But if one day a new generation of New Yorkers would become indifferent to its beauty and ignores the fabulous terracotta plaques and the sunny vistas they portray, if it forgets the legend of the floating dresses of the 19th century – the ship will break the tether and sail away, just like the Crimson Ultimate Insurance tenement in a beautiful Terry Gilliam short film. Just to play it safe, every time I pass by the Flatiron, I tell it that it’s the most beautiful thing in the whole city. I even sigh loudly with delight, not to give it any reason to sail away from us too quickly.

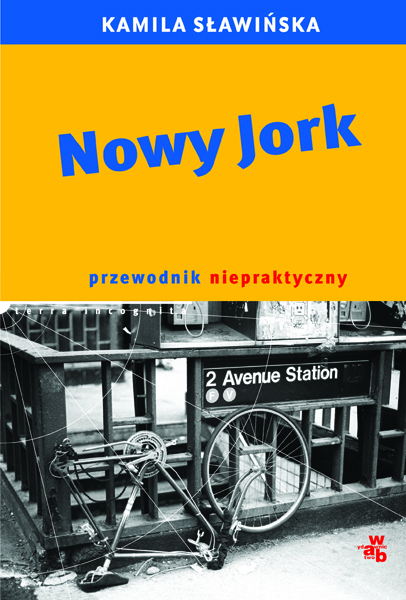

The chapter “The Flatiron Building” is a part of the book “New York: Impractical Guide” by Kamila Slawinska published by W.A.B. Publishing House.

Photo © Book Cover. W.A.B. Publishing House