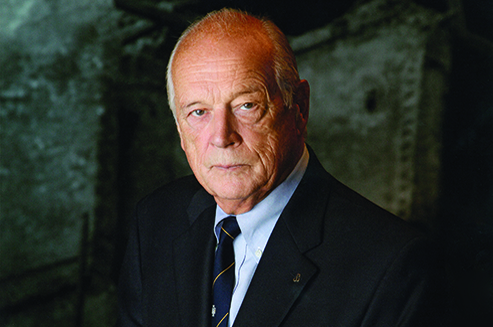

From his early years, Julian E. Kulski was an active member of underground institutions and fought for Polish freedom. Born in 1929 in the Żoliborz district of Warsaw, the son of the capital’s vice-president during the war. Currently living in Virginia, USA, Kulski is a renowned architect and Polish Diaspora activist. He is the author of the book Legacy of the White Eagle and his memoire The Colour of Courage is coming out in the near future.

How do you recall pre-war times, your childhood and growing up in Warsaw?

I was born ten years before the war. We lived in the beautiful district of Żoliborz. I had a very happy childhood. I was a Boy Scout and that helped me a lot in later life as I was prepared for anything. All my family members are heroes – especially my father who was a great role model for me.

What was your father like?

He was born in the Russian Partition. He was not allowed to speak Polish in school. From his early years he and his mother belonged to an anti-tsarist conspiracy. He was one of the first to join the Polish Legions and made friends with Stefan Starzyński, the President of Warsaw, and General Rowecki. Then, he joined the army and took part in the Polish-Soviet War in 1920. He was close to Marshal Piłsudski. In 1939 when the Germans marched in to Warsaw, my father and Starzyński turned the city into a fortress. My father was also the chief of the anti-aircraft defence. When the occupation of the city started, Germans arrested and murdered Starzyński. My dad, as his closest friend and Vice President, wanted to take over his position. He failed to do so, yet he still managed to continue Starzyński’s politics despite being under the official German supremacy of the President of Warsaw, Ludwig Leist. My father was repeatedly arrested by the Gestapo. He survived but he lived in great poverty after the war.

What was his greatest contribution the city?

If it was not for my father and its City Hall, the underground army would not exist in Warsaw. As a former intelligence officer, he received a lot of information about German plans. My father was the President of the city, which meant he wa involved in signing Nazi announcements. The People’s Army had no idea about his connections with the Home Army, and so they organised an assassination attempt. They dropped a bomb on a car he was driving, so after that my dad drove a droshky in the city to show that he was not scared.

What did you do during the war?

I was active within the underground institutions, in the Grey Ranks. In 1941 I got to the Union of Armed Struggle. When I was 12 I made an oath; at first I was a messenger. In 1943, when I was 13, I was arrested by the Gestapo, imprisoned in Pawiak and tortured. Eventually, I managed to escape. I was so angry at what I had seen. I fought in “Provider” (“Żywiciel”), a group at Żoliborz, where I was the youngest member. I was injured while serving there; I received the Polish Cross of Valour and drifted into a camp in Germany.

We know that you managed to escape. How did that happen?

One of the Americans told me to jump into his car and I escaped with him. My father had said that he would not come back to the country until it was free. He advised me to go to London, as my uncle worked in the Polish Embassy there. Later I met two Englishmen who took care of me and helped me to get from Germany to England. I could not say a word in English, and so they dressed me in a uniform, bandaged my throat, and said that I was shot in Tobruk. After that I went to Scotland and I enrolled in the army. But my uncle found out that I was there, and so after a week I was sent back to London. I went to school and learned to speak English. Then I went to Northern Ireland where I finished school. I studied architecture at Oxford, but after a year I obtained an American visa and left, continuing my studies at Yale University. After graduating, I started to look for work and eventually got a position in the World Bank. Over 20 years I was involved in thousands of projects in 30 countries. Apart from that, I was a Professor at three different universities and a Dean in Washington.

You knew and cooperated with great people, heroes such as Jan Nowak Jeziorański and Jan Karski. How do you remember them?

I met Jan Nowak Jeziorański in 1945 and a great friendship grew between us. He even wrote a preface to my book. I had met Jan Karski already in Washington. He told me that my father saved Warsaw and was one of the greatest of Polish heroes.

You are the author of a book which just… disappeared. Tell us the story of that.

I wrote my diary more than a month after escaping from the camp. I simply had difficulties in returning to normal life, and so I did what I was advised by my doctor. I wrote down my memories and cleared them from my mind. Only in 1979, on the 35th anniversary of the Warsaw Uprising, did I decide to publish this book in New York. In its new form it will be published in Poland and other countries under the title The Colour of Courage.

Currently I am greatly preoccupied with activities within American Scouting. These scouts are very interested in Polish Scouting, and, at the beginning, they will be the first readers. My second book The Heritage of the White Eagle is a handbook in American schools. I am often invited to meetings with students. I think that encouraging American interest in Polish culture is my priority at the moment. The Heritage… was also published in Poland last year, with a preface written by President Komorowski.

Speaking of The Heritage of the White Eagle – what are, in your opinion, the outstanding virtues and values of a Polish person?

Surely heroism. Besides, courage, hard work and great doses of capability.

As an architect, how do you evaluate the re-built Warsaw?

Terrible! I am a historic architect. What they did with the Old Town Square and the Royal Castle – it is a miracle and it is beautifully done. But when it comes to buildings from the time of freedom – hotels and the city centre – they have nothing in common with Polish history and Polish spirit at all. Pre-war Warsaw was beautiful because it was homogenous.

What do you think about the current state of things in Poland, how do we use the freedom for which you and other Home Army soldiers fought?

I am very happy with the young, but when it comes to the political situation – we did not fight and spill blood in the Uprising to have people pushing one another around. It is not a Polish virtue and it certainly does not help at all. But I believe that the young generation will set politics as an objective, and set up a party similar to the pre-war governments.

Thank you for the conversation!

Photo © Pangea Magazine