Polish people were welcomed in the Isle of Flowers. It was there, near Rio de Janeiro, where after a long wandering over the sea, the people, who wanted a piece of paradise just for their own, started coming to the land. Their belongings on the back, hope in the hearts, and a vision of fertile fields in minds – that is everything they had.

By the outbreak of the I World War, 130 thousand of Polish people arrived to Brazil. Most of them were peasants, who wanted to improve their fortune. In the 50s of the 19th century, the first inhabitants were the emigrants from Polish lands, belonging to Prussia, but the people coming from the lands annexed by Russia had the largest number of incoming inhabitants – more than 80 thousand. Also many peasants from Galicia migrated to Brazil.

What brought them there? Many of them heard the rumours about a distant land where everyone could lead a wealthy and prosperous life. They also said that the Pope wishes to build a new Catholic country there and he needs the faithful who will inhabit this land. Other rumour said that it was the son of Chancellor Bismarck, full of goodwill towards the Catholics, who is trying to create a country for them where they will have full rights and privileges. The legend, passed from mouth to mouth, from fair to fair, became more popular and colourful, especially that some people, as it later turned out, had their own interest in that.

The largest wave of emigration took place in 1890, when thousands of peasants decided to try their luck overseas. Not only the poorest suffered from “Brazilian fever”, but also the rich ones, because in order to get to the ports in Bremen or Hamburg they needed money. The first people to migrate were those who could afford it. The terrified landowners put more and more pressure on the authorities, so that they would stop emigration, which could paralyse the work in their estates. They forbade cashing goods and chattels, limited issuing the documents – all for nothing. Even groups of hundreds of people managed to pass stealthily between the military police, paving the way with cunning and bribes.

The most important thing for everyone was to get on the ship. With the involvement of Brazil, the emigrants could travel for free. Slavery had just been abolished and the country lacked hands to work. The most welcome were families without small children or elderly people. Those who watched over the recruitment were the emigration agents, who also put a lot of effort to distribute information about all the “wonders” that the new settlers would encounter. Their interest, however, ended as soon as they delivered the man to the Brazilian lands, where they received a fee of around 100 francs per each. Therefore, it was difficult to expect that they were a reliable source of knowledge about the conditions that the immigrants would have to face.

Several weeks on the sea were enough for the weakest to die of exhaustion. Those who managed to survive were supposed to experience a few more disappointments. When they reached the Brazilian coast they had to face the administration and quarantine procedures with no knowledge of Portuguese language. They spent the next weeks in transit camps, where the death rate was also horrifying. Maria Konopnicka in her poem “Mr. Balcer in Brazil,” the new immigrants were welcomed by the words of those who came before them: “Did some impure force drive you here for the final nail in the coffin? It’s a living hell… country of antichrist!”

Finally, the settlers were able to move forward. The local people wanted them working in coffee plantations in the northern-east part of the country, where workers were needed the most. But what Polish peasants dreamt of was a piece of land just for themselves and for this reason they decided to move even further – by carts to the South. In the states of Parana and Rio Grande do Sul the unexplored stretches of forest awaited for them.

The rules by which the settlement was organized were very promising for the Polish pioneers. Each family received 25 hectares of fertile land – the condition was to pay off for the help that was provided in the beginning by the government and a permanent settlement. After about five years, you could become an owner of an enormous farm.

The difficulties, however, were huge. Despite the fact that the land was fertile, it required a completely different technique of cultivation than the one used in Europe. Different climate, wildlife, dangerous animals, diseases – all Poles were put to a hard test. Also the Brazilian officials along with their mess caused conflicts and unexpected complications – the lands were measured with no accuracy or were not measured at all. Many people decided to return to their country.

Every year the bigger part of the settlers became more fond of the Brazilian lands. In their letters they assured their families that it was the land of milk and honey. They asserted that “the horses, cows, pigs, donkeys, chickens, ducks, and geese were bigger than those in Europe.” Although the majority of Polish newcomers were peasants, the first Pole who received the Brazilian citizenship is said to be the engineer Florian Żurowski.

After the revolution in 1905 more educated people came to Brazil. Also at that time Polish people started changing their idea of the Polish diaspora in Brazil, which uses to be only an object of compassion. They began to respect and admire the winners of the Parana wilderness. Even Roman Dmowski visited Brazil. This interest resulted with another, though smaller wave of migration. It was put to an end when the I World War began.

When Poland won its independence, the Polish emigrants were seen as a colony overseas. Brazil again became an attraction for journalists and reporters, such as Zbigniew Uniłowski. They had a rather ambivalent feelings about leaving the regained country. The people also stopped believing in the popular myth of a white explorer and traveller’s ethos.

The well-developing movement of Polish diaspora in Brazil has been pacified with the growth of the nationalist tendencies caused by the global crisis. In the 30’s about 200 of Polish school were closed, only those in the state of Rio Grande do Sul managed to defend. The intellectual revival was brought within the war and post-war emigration, with the representatives of aristocracy, the soldiers who fought in the West and intellectuals. Although Brazil was for many people only a temporary break in travelling to wealthier countries, they contributed many changes to the life of the local Polish diaspora, who led their lives mainly in the provinces.

Since the 50s of the 20th century the Polish emigration to Brazil was rather sporadic. Those who already lived there, became a part of society. The election of the Polish Pope and John Paul’s II popularity in South America increased the national awareness. Today, the number of Polish citizens in Brazil is estimated at over one million people.

We would like to thank the Museum of Emigration for the article.

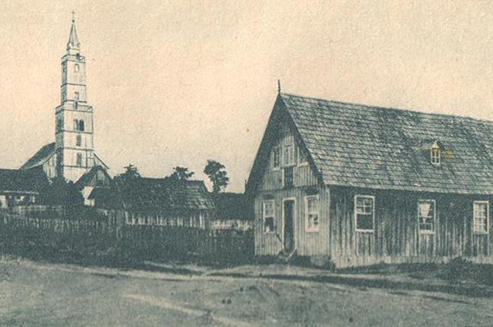

Photograph from the book “Parana. Memories of travel in 1914” by Tadeusz Chrostowski about Polish colonists in Brazil.